Q & A

There have been many misconceptions and mistakes that have been a part of the Eager Beavers legend almost from the start, and persist even now in the most recent accounts. Here I address the most common mistakes, based on the best evidence we have at present.

The publication of Bob Drury and Tom Clavin's Lucky 666, their nonfiction account of the crew, renews a number of these enduring mistakes while introducing a raft of others in terms of its presentation of the history of the crew and in particular the portrayal of Jay Zeamer. It warranted its own critique, which I've done as a blog post here. A summary of the issues can be found in my Amazon review.

Unequivocally no. This is the most enduring and pernicious myth of the entire story. If anything, Jay’s crew members were quite the opposite.

Finding its most recent manifestation in Bob Drury and Tom Clavin's Lucky 666, the characterization originally comes from “Mission Over Buka,” the first chapter of Martin Caidin’s Flying Forts: The B-17 in World War II. Caidin quotes extensively from Walter Krell, a good friend of Zeamer’s dating back to their flight school days in Glenview, IL.

I interviewed Walt Krell myself in 1994. He had been concerned for years about how his casual portrayal of Zeamer and the crew had come across—Krell was never told that he was being recorded—and was relieved at the chance to correct the record on that score. Krell made clear that he didn’t know the crew personally and had only pieced together the story from conversations he had with Zeamer months after the events in question. It's important to note that Martin Caidin never spoke with Jay Zeamer, his crew members, or anyone from Zeamer’s 43rd BG squadrons himself.

Krell stressed that Zeamer himself was certainly no screw-off, and that he was a “misfit” only in the sense that his personality and flying style was a mismatch for the B-26. He was quite well-liked by his cohorts in the 19th Bomb Squadron. “You couldn’t not like Jay,” he said. Krell stressed that numerous pilots never checked out as first pilot in the B-26, including the squadron commander. He went on to describe Zeamer in a letter as “pensive, calm and collected, imperturbable, unexcitable. He never raised his voice, lost his temper, swore, criticized, or found fault with the situation. In his easy-going way he simply accepted circumstances as they arose and met the conditions in his unhurried, deliberate manner. No one ever regarded Jay as not being up to anything but rather above and beyond it. Some kind of a misplaced saint.”

As for the rest of the crew, Krell in our interview said, “I don’t want to use the word ‘renegades.’ I never met his crew.” And indeed they weren’t. Joe Sarnoski and Charles “Rocky” Stone, the core of Zeamer’s initial crew, were the squadron bombardier and squadron navigator, respectively, of the 403rd, flying with the squadron commander until he was lost on a mission. Hank Dyminski was fresh from the States when Zeamer tapped him for his copilot; his first combat mission was with Zeamer. The rest of the crew transferred in from one of two places. Some came from the 8th Photo Recon Squadron as crews with B-17s that were transferred to Zeamer's 403rd Bomb Squadron, while the rest came from the 19th Bomb Group when it ceased operations. When that happened, its newer personnel were sent to other bomb groups where they were unattached to a particular crew until being assigned or selected for one. If that qualifies as “cast-offs” and “misfits,” then there were scores of them in the 43rd Bomb Group in late ’42.

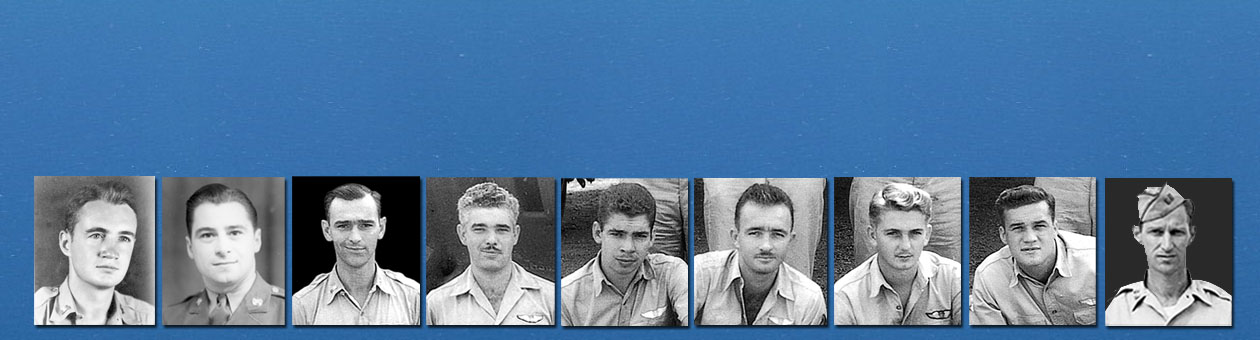

Finally, according not only to their own squadron mates but each other, the men of the Eager Beavers were, by design, much like their pilot: quiet and reserved, good-natured, slow to anger, and tended to get visibly upset only at irresponsible mistakes. Few of them drank, none to excess, and none were carousers. They had their fun—Sarnoski was a bit of a prankster, and Zeamer described George Kendrick as the “spark plug” of the crew who “came up with all the crazy ideas”—but no more than any other servicemen. Certainly nothing to warrant the “screw-offs” characterization.

On the contrary, when Zeamer and Sarnoski were looking for potential crew members, it was the misfits and screw-offs they weeded out. Zeamer himself indicates this in a letter to Agnes Sarnoski in 1943, telling her they ignored those who were inexperienced or hadn't been through gunnery school. Ultimately, though, it's a matter of common sense. It would be the height of illogic that two men with such obvious high standards for themselves would allow "misfits," "screw-offs," and "renegades" on their crew. They were looking for trustworthy men with cool temperaments and a lean-forward attitude to match their own, and that's who they picked.

No and yes. The primary mission, which even General Kenney remembers incorrectly in his memoirs, was the mosaic photographing of the west coast of Bougainville Island, specifically Empress Augusta Bay, to generate the necessary topographical maps for a naval invasion later that year.

The reconnaissance of the airstrip on Buka Island—located just off the northern tip of Bougainville—was a separate mission that was added to Zeamer’s mapping mission at the last minute, first in a phone call Zeamer received the night before the mission, and then quite literally as the plane was taxiing to take off, when a jeep blocked its way to hand off written orders to the pilots. Zeamer ignored both, and only reconsidered the Buka recon when they arrived at the starting point of their mapping run half an hour early. Even then he only decided to do it after the crew assented to it.

It should be noted that Zeamer always considered this a failure of leadership on his part, since it was agreeing to the Buka recon that caused them to be spotted earlier, resulting both in the heavier fighter resistance they encountered and their being caught while still on the mapping run.

No, with an important caveat.

B-17E #41-2666 was not assigned to any particular crew. It was a camera plane and was used as necessary by whatever crew was assigned to use it. Usually this was by the 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron, and often by the same crews who were experienced at such work. Zeamer only piloted 41-2666 five times, two of which were test hops. There are conflicting reports—Jim McEwan of the 8th Photo said that 666 came to the South Pacific with the 8th’s “A” flight—but official indications are that it originally came over with the 19th Bomb Group and was soon after transferred to the 8th PRS. Either way, it was with the 8th that it was flown by different crews before and after Zeamer came across it sometime in the spring of 1943. The plane had indeed been badly shot up in December 1942 on a mission to Kavieng, after which it sat for some time being used for spare parts, but when Zeamer flew it for the first time, the plane he took to calling "Old 666" had already been brought back to flight status and was being flown by the 8th PRS for mapping and recon missions

Now the crew did feel some ownership of 666 considering the work they personally did on it in May and June of ’43 to upgrade it for their needs and for the special hazards of mapping work. But they didn't "rebuild" the aircraft, much less from the ground up. According to Zeamer, the only major maintenance work they did on the aircraft was to replace the engines. The rest of their work consisted of stripping it of unnecessary equipment and installing the additional guns. That didn’t grant them sole use of the aircraft, though, and in any case they were busy with combat missions in other planes they used much more frequently than 666, which again was not a combat aircraft.

It has to be understood that especially in the early going of the bomber war in the Southwest Pacific, there were few enough aircraft that it was not uncommon for crews to share whatever planes were available for duty. As the war progressed and more aircraft were in stock, more consistency was possible, but early on, few crews had a plane they could consider solely their own.

Zeamer’s logbook illustrates the point: He flew or copiloted more than half a dozen different planes while in the 403rd Bomb Squadron. His most common ride was 41-24518,“The Reckless Mountain Boys.” As copilot or pilot, he flew it a total of ten times between October 1942 and January 1943—but only once on a mission. All the rest were errands, local flights, personnel flights, or scrubbed missions.

It was only after the crew got into the 65th Bomb Squadron in April 1943 that they got into a truly routine combat plane, 41-24403, known first as “Blitz Buggy” but in the 65th as “The Old Man.” The Eager Beavers flew it a dozen times starting in mid-April 1943, eight of which were combat missions.

So while the crew did have an affinity and felt some ownership of "Old 666," it was not "their" plane that they used on all of their missions, and rebuilt from the bolts up. It was a specialized plane for a specialized purpose that the Eager Beavers made even more special for that purpose.

Sixteen.

Zeamer wrote sixteen in his personal flight log for the flight, told an Air Force researcher in 1970 there were sixteen guns, and counted sixteen in an interview in 1993. The 65th Bomb Squadron morning report entry for the day also records sixteen.

The only reference to a different number comes from Jay Zeamer's article "There's Always a Way" in the January 1945 issue of The American magazine, in which Zeamer mentions nineteen guns on the plane, which almost certainly counts the spares Zeamer frequently mentioned the crew carried in the waist in case of jams.

The only remaining confusion on the issue of the gun complement—and there isn't really—is where those sixteen were located. Zeamer confuses the issue to some degree by occasionally mentioning a .50 through the bottom of the plane aft of the belly turret, but that can't be reconciled with sixteen mounted guns and the gun complement described by navigator Ruby Johnston in his combat diary, in which he explicitly records four single .50s in the nose compartment—one in each cheek, one through the Plexi for Sarnoski, and one mounted to the deck next to Sarnoski for Zeamer to fire—plus twins on each side of the waist. Counting the twins in the radio room that both Zeamer and radio operator Bill Vaughan recall, that makes sixteen. There simply is no accounting for the bottom-firing gun Zeamer mentions. It's been suggested, plausibly, that Zeamer was simply remembering a similarly positioned .50 on the B-26s he flew prior to switching to B-17s.

It should be pointed out that even adding such a gun would only raise the complement to 17, a number never mentioned anywhere. Sixteen guns is the only number repeatedly given in contemporary and later accounts, and that matches the documentary evidence.

Yes, the plane was named "Lucy," by Zeamer himself, according to Zeamer himself, but he and the crew continued to refer to it as "666" or, in Zeamer's case, "Old 666."

In an August 1943 letter to journalist Art Cohn, author of the "Z Is for Zeamer" article in the January 1944 issue of Liberty Magazine, Zeamer tells Cohn that the name “Lucy” was for a girl who lived in Washington, D.C. This would have been Lucile Christmas, daughter of Major General John K. Christmas, who Zeamer dated briefly while he was at Langley.

This aligns with a 65th crewman’s combat log entry, provided to me by author/historian Steve Birdsall, for September 25, 1943, which notes the mission plane as “666 ‘Lucy’ B-17.” Birdsall also provided a photo of a 65th squadron B-17 with “Lucy” nose art.

The confusion stems from timing. Under Zeamer’s command, 41-2666 was likely only named "Lucy" at most for two weeks prior to the 16 June 1943 mission. The crew itself, according to my interviews with the surviving crew members, only ever referred to the plane as “666” or simply “the plane.” Zeamer clearly felt a deference both to Ms. Christmas, initially, and later to his wife Barbara, in only referring to the plane as "666" or "Old '666."

It has been reported on occasion that copilot J.T. Britton was injured, most recently in Drury and Clavin's Lucky 666, but multiple sources—including Britton himself—say he wasn't.

Ruby Johnston, the navigator on the mission, said in our interview that Britton was not wounded, but more important, Britton himself never indicated in multiple conversations with me that he was hurt in any way on the Bougainville/Buka mission. When I read him my account of the mission, in which I portray him as uninjured and aiding Zeamer at the controls, he did not correct me. If he did receive a head contusion as described in Lucky 666, it would be despite wearing his helmet pulled low on his head, as both he and Zeamer did, again according to Britton himself.

It has always been a dubious claim in light of the fact that it would have been practically impossible for Zeamer, wounded as badly as he was, to pull 666 out of the severe dive after the initial attack without assistance. The B-17 has no boost, hydraulic or otherwise, on its controls; they are strictly cable-actuated, requiring brute strength to pull out of any excessive maneuvers.

Britton did indeed have Johnnie Able, Jr., normally the belly turret gunner but substituting for Bud Thues in top turret on that mission, pilot the aircraft for about ninety minutes on the return flight. It was Britton, however, who landed the plane at Dobodura, expertly so and without incident, despite having to ground-loop it—steering the plane off the runway in a wide loop to slow it down. A truly impressive feat considering the hot landing without brakes or flaps. Britton was rightly proud, telling me, "I just greased 'er in. It was one of the best landings I ever made."

A few, now, but none with respect to the 16 June 1943 mission. It took decades for any to surface. In recent years, though, a few have been found, with interesting stories attached. They can all be seen in the history of "Old 666" on the site here.

His original nickname was "Pughie," but Johnnie Able refused to call him that. He went with "Pudgy" instead, which became “Pudge.” This is even how Able refers to Pugh in his official statement given in support of Zeamer’s Medal of Honor. Considering Herb Pugh wasn't heavy—on the contrary, was quite the fitness nut like Zeamer—it says something about him that he took all of his nicknames in stride.