"Old 666" / "Lucy"

A History

B-17Es under construction at Boeing Plant 2 in Spokane, WA, in December 1942.

(USAAF via Wikimedia Commons)

The history of B-17E #41-2666 is, like most of the Pacific Fortresses, a patchwork. (Its nicknames “Old 666” and “Lucy” came toward the end of its tour of duty.) Especially in that theater of the war, during that time period—the early days of the bomber war in the southwest Pacific—official records are scant. Thus the most that can be done is to piece together what we can from available official records, mission diaries, and flight logs. Individual recollection can be helpful, but to the degree they’re in conflict, it must give way to the official and contemporary records.

The official record tells us that 41-2666 was built at Boeing Plant 2 in March 1942. The “E” model represented the most dramatic upgrade in the B-17 series, the first to feature the elongated fuselage that allowed for a tail gun, as well as the distinctive dorsal fin leading to the larger tail. The B-17E was the first variant to be produced in mass quantity—though not remotely to the scale of the “F” and “G” models—beginning in the fall of 1941 and the next summer.

Upon completion, 666 was delivered, likely by the ferrying division of the Air Corp’s nascent Air Transport Command, to Minneapolis, probably to Wold-Chamberlain Field, on March 9, 1942. From there the aircraft was flown to Hawaii in May 1942, destination Australia. Unassigned to a particular squadron, it was to serve as a replacement for the battered B-17s of the early Philippines and East Indies campaigns.

By mid-May it was in Australia, assigned to the 435th Bomb Squadron of the 19th Bombardment Group. It was with the 435th that it appears to have experienced its conversion to a specialized reconnaissance aircraft. There’s reason to believe some portion of the equipment, possibly the high-precision mounts, might have been installed before 666 left the U.S. Sixteen B-17s had modification work done by Mid-Continent Airlines in Minneapolis in April 1942, the same time that 666 would have been there, which makes it a possibility. Whatever the case, it appears at least the cameras themselves were installed in Australia, likely at Laverton or Charters Towers, around the beginning of June. “Our new airplane is acquiring some fifty thousand dollars worth of cameras,” a 435th diarist wrote on May 30, 1942, “replacing former P 38 [sic] reccos, those ships too often failing to get back with the pictures.”

Different camera configurations were used for different types of reconnaissance, and still another for photo-mapping work, in which an array of photos from a fan of cameras was stitched together to form a wide-area image of a target. The fact that the diarist refers to “cameras,” plural, though, implies that it was to the latter he was referring for Old 666. Such a set-up, referred to as “trimetrogon,” consisted of a trio of Fairchild K-17 cameras using 6” Bausch & Lomb “Metrogon” lenses in a fan array that allowed for horizon to horizon coverage on 9” x 9” negatives. All of the cameras used vacuums to flatten the film negative, and could be operated manually or automatically by an electronic variable shutter control. At 20,000 feet, the end result was, ideally, a seamless, sixteen-mile wide map of the target area. Such mapping required high-altitude, straight and level flight for an extended period of time, and was thus among the most dangerous type of photo work, especially if needed deep in enemy territory.

In most F model and later Fortresses modified for the tri-met system, this camera array was installed in the nose, with more cameras occasionally added in the bomb bay. In 666, however, as well as in at least one other B-17 modified for recon/mapping work early in that theater, the arrangement consisted of a camera mounted beneath the radio compartment pointing straight down, with the other two cameras mounted opposite one another, aft of the waist windows, each angled 30° below the horizontal axis. (For general reconnaissance photography, typically either a K-17 or K-18 with a 12" or 24" focal length were used, mounted in the vertical mount amidships or literally handheld through a waist window, with the camera mounted on a flexible mount or strapped to a crewman who was himself strapped in.)

With the records currently available, it appears Old 666's first mission came on June 8, 1942, a recon of the New Guinea coastal town of Lae. The next appearance it makes is in the diary of the 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron, the recon photo outfit of the 5th Air Force. The 8th worked closely with the 435th Squadron of the 19th Bomb Group, what with both being stationed in Townsville, a small town on the northern Australian coast that became one of the major Allied bases in the South Pacific. In theory, the 8th provided the film, equipment, and at least the photographer and gunners for recon and mapping missions, and the 435th the officer component, but in practice there seems to have been a mutual arrangement as to who actually provided the enlisted crew.

On July 11, an episode occurred that adds some additional confusion to 41-2666’s already patchy history. It seems a life raft managed to come loose and inflate while 666 was in flight, and blew out the waist window, damaging the tail of the airplane. This mirrors a similar report from the combat diary of the 65th Bomb Squadron, part of the famed 43rd Bomb Group. On November 4, on the outward bound leg of a bombing mission to Lae, one of the life rafts on board the bomber on that mission accidentally deployed at 15,000 feet. The raft blew out the waist window, ripped off the radio antenna, and wrapped itself, still fully inflated, around the port elevator. The pilot dropped 666 down to almost 9,000 feet and one of the gunners successfully deflated it with a side gun. Unfortunately the raft remained wrapped around the elevator, which was damaged enough at that point to warrant aborting the mission. They landed safely at 7-Mile Strip outside Port Moresby, the raft still attached to the elevator. The bomber has been reported as having been Old 666, but we have no confirmation of that bomber’s serial number. We only know for certain that the July 11 incident involved 666. It’s possible that such an unusual event means both incidents happened to the same aircraft, but until further information comes to light, we simply don’t know.

Regardless, that it did happen at least once for certain in 666 didn’t help its reputation. Well before "Old 666," the aircraft became known as a "Hard Luck Hattie" for the frequent damage it incurred, battle and otherwise. It's possible that it was already fostering that reputation by late July 1942. The 8th Photo reports that on July 27, 666 was flown to Charters Towers "to be overhauled." Since cameras had already been installed, this implies a mechanical overhaul, perhaps because of the damage from the life raft.

While 666's record card never shows it being officially transferred to the 8th Photo, the 8th certainly considered it to be, as well as the two other B-17s in service to it. That belief is manifest in the 8th’s squadron diary entry for September 5, which saw "the last of the B-17 as an Eight Photo aircraft. Air Force today transferred the B-17s to the 435th Bomb Squadron."

This certainly seemed to be the case for 666. Nothing is known about the plane for the next month. It’s possible that it was the aircraft involved in the November 4 life raft incident in the 65th, but what we know for sure is that on November 8, it was back in Townsville and gone for another mission with a 435th Bomb Squadron crew flying a mission for the 8th Photo. The object was to photograph Rabaul and its harbor. After arriving in Port Moresby, however, it was determined that 666 was carrying the wrong cameras for the mission, and the crew flew it back to Townsville.

That same evening it was flown by a different crew up to 14-Mile Strip, another airdrome near Port Moresby which was the home of the 8th Photo. The pilot, scheduled to return home soon, refused to fly any dangerous long-range missions into enemy territory, and once again flew Old 666 back to Townsville. Most of the 19th Bomb Group, including the 435th Bomb Squadron to which 666 had been assigned, returned home a few days later, stranding the plane in Townsville.

Considering airworthy B-17s were at a premium at the time, it probably didn’t gather dust for long. By December 20, it had found a home with the 403rd Bomb Squadron, another of the 43rd Bomb Group squadrons. Considering the 403rd was based at Iron Range, just three flight hours up the coast from Townsville, in mid-November, it’s not unreasonable to believe 666 found its way to the 403rd even earlier. It’s also likely that it was with the 403rd that 666 made the trip from Townsville to Milne Bay, the 403rd’s next duty station, located on the southern tip of New Guinea, the end of November.

On December 20, a 403rd crew—coincidentally the same crew that, before transferring from the 435th, had flown 666 to Townsville to get the cameras changed in November—took it on a mission, the nature of which is unknown. The next mission, however, two days later, we do know about, due to an exciting account of it by the belly turret gunner. Returning from a recon of the Rabaul airfields, the crew was caught by surprise by a couple of Zeros and 666 was badly damaged: two gas tanks and the #2 gas tank and oil cooler holed, the left aileron and right elevator controls shot out, and the main rib in the right wing shot out as well. Not to mention, as the belly turret gunner, who also lost his left gun, wrote, “plenty of 15 mm holes all over. It was a very, by-God, hot time."

If later reports of the plane needing a wing replaced are true, this is likely the mission that did it. It certainly would have needed some serious work to become airworthy again, but considering its specialized nature and the sheer expense already sunk into it, it’s hard to believe that it would have been left to sit for salvage, as later accounts about Zeamer’s crew portray. Whatever the case, Old 666 isn’t mentioned again by the 8th Photo until April 11, 1943, when the 8th used it to photograph Japanese air bases at Kavieng. Once again 666 got jumped, this time by as many as ten Zeros, but due to the expert flying of the pilot, for once it was only lightly damaged.

Four more missions with the 8th followed in April and May—another to Kavieng, one to photograph the Yellow and Sepik rivers of New Guinea, a trip to Wewak airdrome, and finally to Lorengau on distant Manus Island for reconnaissance and mapping. Pointing up the frustrations of such work, problems with either the recon photos or mapping equipment were encountered every time.

Sometime during the previous months, 41-2666 had been assigned to the 65th Bomb Squadron. At the conclusion of the last mission with the 8th on May 14, Old 666 was returned to the 65th, much to the 8th’s satisfaction. “We are happy that Hard Luck Hattie has been returned to the 65th Squadron,” wrote the 8th Photo diarist. As it turned out, the squadron executive officer of the 65th was just as happy.

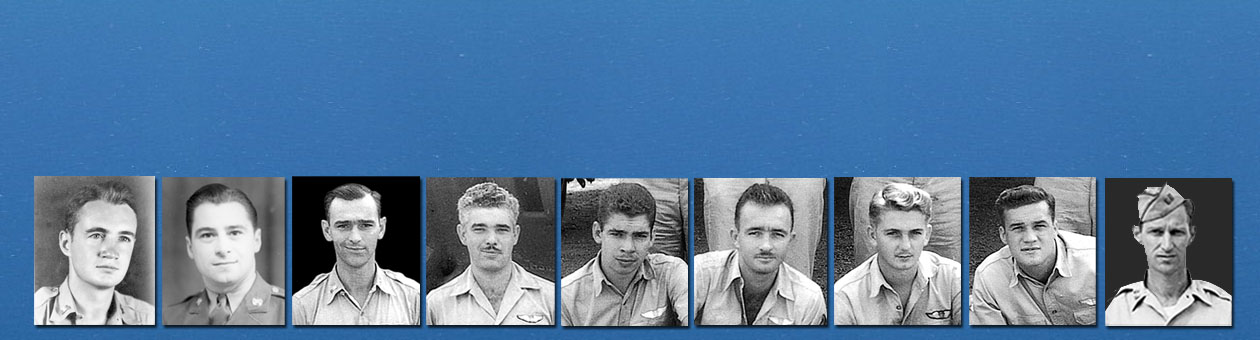

His name was Jay Zeamer, and when his photographer and side gunner George Kendrick, formerly of the 8th Photo (as were two of Zeamer’s other regular crew members), mentioned that this specialized aircraft was in the squadron, Zeamer jumped at the opportunity. Zeamer and his crew had a reputation for flying as often as they could, volunteering for missions as they came available. Here was an opportunity to be up even more.

Zeamer immediately used his position to have Old 666, as Zeamer took to calling it (to the crew it was simply “666” or “the plane”), hauled to a revetment where his crew could work on it. Combat missions in other aircraft kept them busy, but over a couple of days prior to a test hop on May 18, and then a week off soon after, Zeamer reported that his crew stripped almost two thousand pounds of weight, including cartridge belts and ammunition feed equipment, from the B-17. They would feed the guns directly from boxes of 250-.50 caliber rounds set beneath the guns. They also replaced all four engines. Considering the dangers of long-range mapping, Zeamer wanted a fast ship.

He also wanted it well-armed, and it was in that department that Old 666 became justifiably famous. Taking a cue from other pilots before him, namely his late friend and 43rd legend Ken McCullar, Zeamer had a fixed .50 installed in the nose, mounted to the bombardier’s deck, wired so that he could fire it from his control column. It would give him “the fortitude,” as he would later put it, to face enemy fighters when they inevitably made their head-on passes on the B-17’s historically weakly defended nose.

What made 666 truly unique, however, was the addition of twin .50s not just in the radio room, which had been done occasionally by Fortresses in the 19th Bomb Group, but twin .50s on either side of the waist. This was a singular feat of field engineering, difficult enough that it has drawn understandable skepticism from more than one B-17 expert. While we don’t have photographic proof, we do have the testimony not just of Zeamer but his flight engineer and tail gunner that they did indeed have twin guns in both waist positions. Not only that, both Zeamer’s log book and the 65th squadron morning reports list Old 666 as having sixteen .50s on board. Those additional four guns on 666—Zeamer’s extra in the nose, plus the additional gun in the radio and both waist positions—added to the fairly standard complement of twelve on Pacific B-17s (which included a flexible .50 in the nose in addition to the single cheek guns), gives a total of sixteen guns. (Reports of nineteen can only include the spare .50s Zeamer instructed his well-prepared crew to have on hand in case of jams.)

Zeamer and the crew almost immediately went to work in the plane, with far better luck than most crews had had in 666. On May 28, 1943, the crew made two mapping runs on New Ireland, sighting a new Japanese airstrip and a three-ship convoy. On June 2, they successfully mapped the Admiralty Islands and made a reconnaissance of a small Japanese airfield off Buka Passage, the small strait separating tiny Buka Island from the northern tip of Bougainville in the Solomons.

Around June 14, Zeamer, apparently considering the plane enough their own to warrant it, commissioned a 65th artist to paint the name “Lucy” in script on the port side of the nose, mostly between and underneath the small forward window and enlarged gun window on that side. The name came from a young woman named Lucile who Zeamer had dated at Langley in spring 1941; his reticence later regarding the name of the plane came from his desire not to attract unwanted attention to her. It was not a name the crew ever used for the plane itself, as they never had the opportunity. (The title of a recent book about the crew from Simon & Schuster, Lucky 666, has caused further confusion about the name. “Lucky 666” is strictly a modern invention of the authors for that title; it was never a name or handle given to the aircraft.)

Likely Old 666 after its famous mission, judging by the aft camera windows and damage around the nose. The "Zeamerized" additional guns have been removed.

(USAAF via Dan Johnson)

On June 16, Zeamer and his crew, with a couple of substitutes, took 666 to Bougainville and Buka again on the mission for which they and the plane would become famous. Once again, surely due to its specialized nature, despite again incurring serious damage—four or five 20mm cannon holes, almost two hundred bullet holes, oxygen and hydraulic lines pierced, an oxygen fire, the pilot’s instrument panel and rudder pedals destroyed—666 was restored to flight status.

Once again, too, the camera plane was assigned to the camera squadron. The extra armament that Zeamer’s crew had added was removed, probably as too heavy and, especially in the case of the twin .50s in the waist, ungainly and unreliable. After a few months with the 8th Photo, it was reassigned one last time to a combat squadron, this time to the 63rd Bomb Squadron, which had yet to convert to the B-24 as the rest of the 43rd already had. The 63rd squadron diary records only two missions that it flew 666, both in late September 1943.

After that, the history of the plane again goes dark again, for five months, until #41-2666 is shown finally being returned to the U.S. in March 1944. It landed first at Spokane Army Airfield, where on March 22 it was assigned to the base administration of Air Technical Service command. It didn’t stay there long, its usefulness for training purposes prompting reassignment on July 4, 1944, to the heavy bomber component of the Combat Crew Training Station at Walla Walla Army Air Base.

Training at Walla Walla, however, leaned toward the longer-range B-24, which had largely replaced the B-17 in the Pacific and was increasingly being used in Europe. As a result, the obsolete #41-2666 was transferred after just three weeks to the Southeast Training Center at Hendricks Field in Florida. It would spend its remaining days there being used for the specialized four-engine flying training program for first pilots.

In August 1945, Old 666 was flown to Albuquerque, among the first of over fifteen hundred bombers, fighters, and trainers to be parked around old Oxnard Field, sold as scrap metal to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. In a sense it had come full circle, as the 19th Bomb Group to which 666 had long been attached had been the first bomb group stationed at nearby Albuquerque Army Air Field when it was activated in 1941. By the end of 1946, the old bomber that had survived so much damage in its career met its final match, and was smelted down for aluminum, scrap iron, and copper wire. It was a tragic end for such an historic aircraft, and for aviation in general. Today only four complete B-17E airframes exist, and only one currently available for public viewing. Here’s hoping the other three join it soon.

Special acknowledgement for this article is due Steve Birdsall and Chuck Varney.

I provide this information as a public service, but it is the product of thirty years of research. If you reference it, a simple attribution or reference would be much appreciated.

Think this story should have its own miniseries or movie?

Help make it happen by signing the petition here!

Sources

Steve Birdsall, author/historian/filmmaker

Chuck Varney, historian

Interview, T/Sgt. Jim McEwan, 8th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron

Interview, Col. Ruby Johnston (regular crew, Zeamer’s Eager Beavers)

Interview, S/Sgt. Herb Pugh (regular crew, Zeamer’s Eager Beavers)

Interview, son of E.F. "Bud" Thues (regular crew, Zeamer’s Eager Beavers)

Personal flight log, Jay Zeamer Jr.

Letter, Jay Zeamer to Art Cohn, 10 Aug 1943

Morning reports, 403rd Bomb Squadron, 43rd Bomb Group

Pay Reports, 8th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron, 6th Reconnaissance Group

Combat diary, William Eaton

“Sebring Air Terminal,” Allen C. Altvater

"The Modification of Army Aircraft in the United States, 1939–1945," AAF Historical Studies No. 62, 1947

"A History of Kirtland Air Force Base: 1928-1982," Don E. Alberts & Allan E. Putnam

The Eight Ballers - Eyes of the Fifth Air Force: The 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron in World War II, John Stanaway & Bob Rocker

Military Aircraft Boneyards, Nicholas Veronico & A. Kevin Grantham

AeroVintage.com

American Air Museum in Britain

JoeBaugher.com

Pacific Wrecks

USAF Orders of Battle

United States Air Force (af.mil)